India’s Green Hydrogen Ambitions: Can Its Certification Framework Support Global Trade?

India’s National Green Hydrogen Mission (NGHM), launched in January 2023, marks a pivotal shift in the country’s decarbonization strategy. With its ambitious goals, India aims to become a global supplier of green hydrogen. The Green Hydrogen Certification System (GHCI) provides the technical foundation to validate hydrogen as “green” under strict emission and energy sourcing rules.

This article provides a focused overview of NGHM and GHCI for industry and policy stakeholders.

Why Green Hydrogen Matters

Green hydrogen, produced via electrolysis powered by renewable electricity, is critical for India’s decarbonization journey. It enables deep emissions reductions across hard-to-abate sectors such as steel, fertilisers, refining, chemicals, long-haul transport, and shipping. Additionally, it plays a vital role in energy storage, grid balancing, and facilitating cross-border renewable energy trade.

According to the NGHM, green hydrogen represents a multi-trillion-dollar global market opportunity, and India aims to capitalise on it by producing 5 MMT annually by 2030, with the potential to scale up to 10 MMT. This could generate over 600,000 jobs, reduce 50 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions annually, attract major investments in electrolyser manufacturing and renewables, and cut fossil fuel imports by ₹1 lakh crore each year, strengthening India’s energy security and positioning it as a global green hydrogen leader.

Green Hydrogen Certification System (GHCI)

India’s certification journey began with the release of a Draft GHCI in September 2024, which outlined proposed rules, emission limits, verification procedures, and certificate types. Following stakeholder feedback, the Final GHCI was issued in April 2025. While the final version retained the core framework and refined provisions related to certification timelines and compliance enforcement, it did not fully align with global best practices such as the EU RFNBO and US 45V frameworks. Specifically, GHCI does not mandate requirements like hourly matching of renewable electricity, additional /new renewable electricity capacity, or geographic proximity, which are becoming essential for accessing regulated export markets.

Overview of GHCI

The GHCI verifies that hydrogen meets defined emissions intensity and renewable electricity sourcing criteria. Certification is mandatory for all domestic producers availing incentives, while producers generating less than 10 tonnes per year may certify voluntarily. Producers with 100% export orientation and no subsidies are only required to report production and emissions.

Key institutions involved include the MNRE for policy oversight, an Implementation Agency for managing the certification process, Accredited Carbon Verifiers (ACVs) for independent verification, and a Technical Committee for reviewing and approving final certifications.

GHCI outlines four certification types to support project development: a Concept Certificate (optional, design-stage compliance), a Facility Certificate (mandatory for operational readiness), a Provisional Certificate (optional, for monthly self-reporting without carbon footprint verification), and a Final Certificate (mandatory for green hydrogen claims, based on third-party annual verification).

Renewable Electricity Sourcing Rules

GHCI specifies pathways for sourcing renewable electricity to ensure credible green hydrogen production. These rules promote traceability between renewable energy procurement and hydrogen production, while excluding instruments like unbundled Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) and carbon offsets.

Acceptable RE sourcing options under GHCI include:

- Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs): Through dedicated transmission lines or the shared power grid.

- Electricity from Energy Storage Systems: When charged exclusively from renewable sources.

- Green Day-Ahead Market (G-DAM) Purchases: Market-based procurement of renewable power.

- Green Tariff Mechanisms: Offered by distribution companies (DISCOMs).

GHCI allows the use of grid-banked renewable electricity if aligned with applicable regulations (Clause 9.1), providing operational flexibility by enabling producers to utilise renewable electricity stored virtually into the power grid during periods of surplus generation and draw it later when direct renewable supply is unavailable. This helps maintain continuous hydrogen production without requiring real-time renewable electricity availability or costly on-site storage solutions.

Under India’s Open Access framework, this banking typically follows a 15-minute block matching system, where banked renewable electricity must be consumed in the same 15-minute time block across different days within the year (varies across states). While this provides some temporal alignment, it does not ensure real-time clean energy consumption and may not meet emerging international standards for hourly matching.

Further, with many states tightening banking provisions, moving from annual to monthly settlements, and restricting withdrawals during peak hours, this flexibility is expected to reduce over time. Producers may increasingly adopt Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) as battery storage costs decline to ensure continuous hydrogen production without relying on grid-banking services.

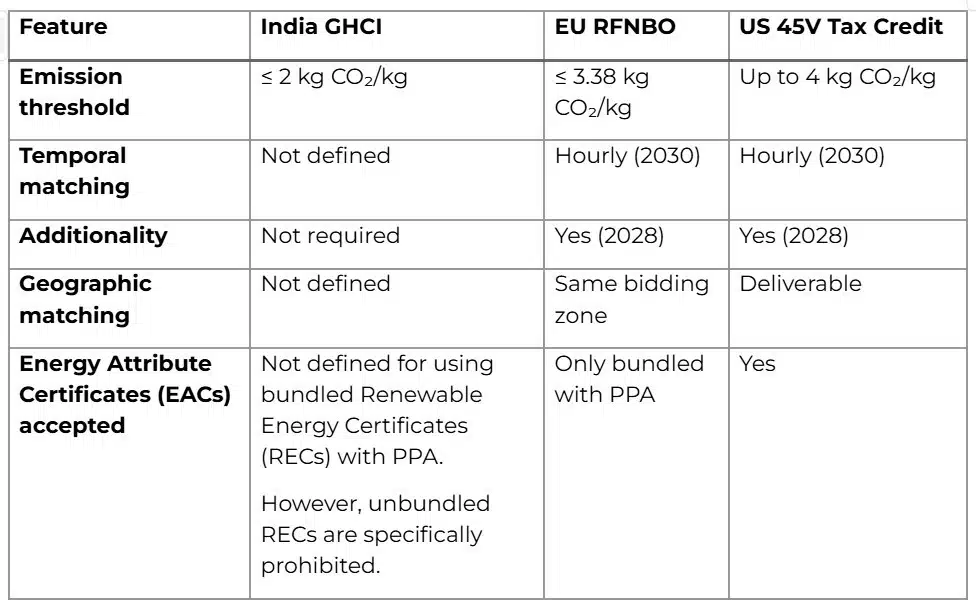

Comparison with Global Standards

As international demand for green hydrogen grows, countries are adopting their certification frameworks with varying levels of stringency. This section compares India’s GHCI with two influential global mechanisms: the European Union’s Renewable Fuels of Non-Biological Origin (RFNBO) rules and the United States’ 45V Clean Hydrogen Production Tax Credit. The comparison focuses on key eligibility criteria, especially around emissions thresholds, and clean electricity sourcing and matching requirements.

In India, additionality is often achieved in practice as most renewable energy producers prefer the Captive Open Access (OA) model to avoid cross-subsidy surcharges, leading to the development of new captive renewable electricity projects. While geographic proximity is a key requirement under EU and US schemes, India’s unified national grid and the availability of renewable electricity across states via the Inter-state transmission system (ISTS) network make this less of a constraint for domestic hydrogen production.

Key Divergences in Temporal and Geographic Matching Requirements

While India’s GHCI sets a stricter emissions threshold (≤ 2 kg CO₂/kg) compared to EU (≤ 3.38 kg CO₂/kg) and US (Up to 4 kg CO₂/kg) schemes, it does not yet mandate additional renewable energy capacity and temporal and geographic matching of renewable electricity, which are key export market requirements under EU RFNBO and US 45V schemes.

A stricter emissions threshold, when calculated using average grid emission factors, does not guarantee that hydrogen production is powered by clean electricity at the time of consumption. It only reflects a grid emission average, which can mask real-time fossil fuel usage.

In contrast, temporal matching combined with additionality ensures that hydrogen is produced using real-time renewable electricity from new capacity. Temporal matching is conceptually similar to India’s established practices of round-the-clock (RTC) and Firm and Dispatchable Renewable Energy (FDRE), where renewable supply is closely aligned with actual consumption in real time.

A recent U.S. study (“Minimizing Emissions from Grid-Based Hydrogen Production”, Environmental Research Letters, 2023) shows that without hourly matching and additionality, grid-based hydrogen production can result in emissions levels comparable to or even exceeding fossil-based methods under certain grid conditions. Requiring real-time clean electricity from new renewable capacity significantly lowers emissions and supports genuine decarbonization. The study also finds that enforcing hourly matching adds a modest cost, less than $1/kg H₂, and potentially near zero when firm clean energy resources are available.

Though some hydrogen producers in India may invest in new Captive Open Access projects, meeting the additionality requirement, this is not mandatory under GHCI, and many may continue sourcing from existing renewable projects via PPA or G-DAM/Green Tariff mechanism.

This lack of clear requirements for additionality and temporal matching could impact the credibility of India’s green hydrogen in export markets.

Note: Although the 45V applies only to US producers, similar standards could apply to imports. Both schemes aim to ensure green hydrogen is truly emission-free and drives new RE deployment.

Case Study: Gentari and AMG Ammonia Sign Landmark RTC Green Energy Agreement

Despite the current GHCI framework, some Indian companies are proactively aligning with international standards to unlock export markets. One such example is AM Green Ammonia project.

In December 2024, Gentari and AMG Ammonia signed a firm Power Purchase Agreement to supply 650 MW round-the-clock (RTC), carbon-free renewable energy for AMG Ammonia’s upcoming green ammonia facilities. This agreement aligns with EU RFNBO requirementsand represents one of the largest such projects globally.

Gentari will develop approximately 2,400 MWp of renewable capacity, integrated with 350 MW / 2,100 MWh of energy storage, ensuring a firm and dispatchable green power supply that meets stringent hourly matching requirements.This pioneering arrangement enables AMG Ammonia to scale production to 5 million tonnes of green ammonia annually by 2030, equivalent to 1 MTPA of green hydrogen, positioning India as a major global supplier of clean fuels.

Implications of Non-Alignment with Global Best Practices

Trade and Market Risks:

- Limited Export Access: While GHCI is primarily designed to support domestic hydrogen producers, its certification is unlikely to meet the requirements of high-value export markets like the EU and US, which mandate stricter criteria such as hourly matching and additionality. Export-oriented producers will still need to pursue internationally recognized certifications to access these markets.

- Investor and Buyer Preferences: Global investors and multinational companies operating in India may favor hydrogen certified against international standards to meet their own corporate decarbonization and reporting commitments, potentially influencing offtake agreements and financing decisions.

- Certification Complexity: GHCI exempts 100% export-focused producers without subsidies from mandatory certification, allowing them to comply directly with importing countries’ standards. This approach aligns with the NGHM’s broader objective of focusing public support on domestic consumption. However, producers targeting both domestic and export markets must navigate dual certification requirements, increasing compliance costs and administrative complexity.

Strategic Consequences:

- Reputational Considerations: While GHCI serves India’s domestic needs, flexible rules without strict additionality and temporal matching may raise concerns about the environmental integrity of Indian green hydrogen, even for domestic buyers pursuing ambitious climate targets.

- Policy Disconnect: Although the NGHM outlines strong export ambitions, the current design of GHCI primarily supports domestic decarbonization goals. Unless the certification framework evolves to align with global market requirements, India’s ability to competitively supply green hydrogen to export markets may remain limited.

- Missed Leadership Opportunity: Without adopting advanced certification standards, India risks falling behind as other countries position themselves as leaders in supplying premium, low-carbon hydrogen to global markets.

Path Forward

Aligning GHCI with international norms, especially for export-focused projects, would ensure India remains globally competitive in clean hydrogen markets.

India’s NGHM and GHCI provide a robust starting point to scale green hydrogen. As the global market evolves, periodic upgrades to India’s certification framework, especially in areas like hourly matching and additionality, will be important to preserve export readiness and climate credibility.