CBAM 2026 and the “Physical Hourly PPA” Shift

From 1 January 2026, the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) moved from a reporting phase to a binding system. Emissions are no longer just disclosed; they now directly affect how many CBAM certificates must be purchased, and therefore how much exporters pay.

For Asia-Pacific (APAC) companies selling into Europe, CBAM is often seen as mainly affecting steel, aluminum, or cement. That is partly true — the bigger issue is electricity,1 which is explicitly covered under CBAM, and is also a major source of emissions in many CBAM goods. Under the EU rules, companies cannot simply rely on annual energy attribute certificates to lower their reported emissions. To move away from default grid-average values, they must show that cleaner electricity was physically supplied and matched in time to production.

Why Should APAC Care?

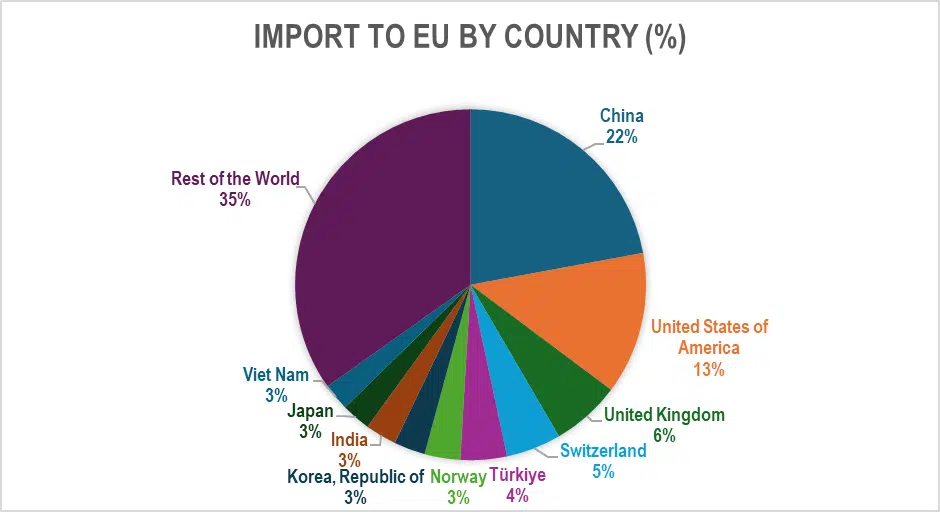

In 2024, the EU imported approximately USD 2.39 trillion worth of goods. As the chart shows, China is by far the EU’s largest external supplier, accounting for 22.2% of total imports (USD 530.6 billion). Among other Asia-Pacific economies, the Republic of Korea (USD 69.4 billion), India (USD 68.6 billion), Japan (USD 64.5 billion), and Viet Nam (USD 58.7 billion) each represent meaningful shares of EU import exposure.

Taken together, these five APAC economies alone account for USD 791.8 billion, roughly 33.2% of total EU imports. This means that one-third of the EU’s import exposure is concentrated in major Asian trading partners, underscoring how CBAM rules, including electricity-related requirements, will directly influence competitiveness across the region.

Source: EnergyTag.

The Electricity Twist: Default Values vs. “Actual Values” Is Not Optional

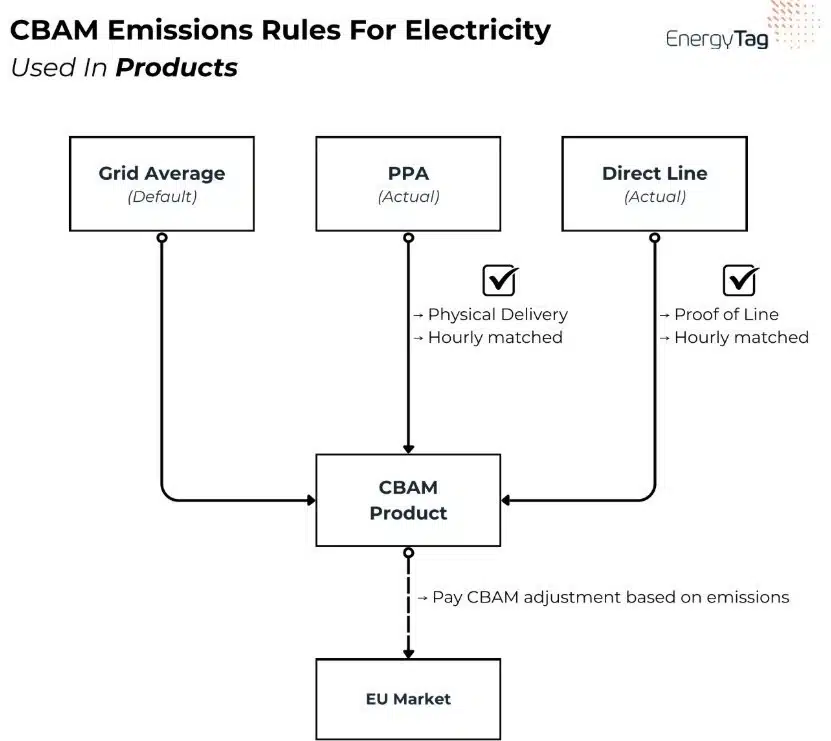

CBAM’s electricity rules are built around a strict hierarchy:

- Default values (grid-average logic) apply automatically.

- Actual embedded emissions can be used only if strict criteria are met (with verification).

This default-first logic is explicit in CBAM’s framework for electricity and embedded emissions calculations.

Why does this matter? If you’re a producer (or an EU buyer sourcing from a producer) whose electricity supply is cleaner than the country’s grid average, the only way to reflect that advantage is CBAM’s evidence requirements. That’s where PPAs, deliverability, and hourly matching enter the picture.

CBAM Basics: What Is New in 2026

CBAM is introduced by Regulation (EU) 2023/956 and applies to certain goods: cement, iron & steel, aluminum, fertilizers, hydrogen, and electricity. Although electricity is a covered sector, its main importance is that it contributes significantly to the emissions embedded in other CBAM goods. In the initial phase, CBAM covers electricity emissions for cement, fertilizers, and electricity, with other products expected to be phased in later. According to the European Commission’s 2026 operational guidance, CBAM is now fully operational. This means reported emissions, including those linked to electricity use, directly affect the amount payable at the EU border.

The legal obligation to submit CBAM declarations and surrender certificates lies with the authorities of EU importers (CBAM declarants) or their customs representatives. However, the responsibility for providing emissions data – particularly on electricity consumption metering, and supply – effectively falls on non-EU producers. Without this information, their products may be less competitive in the EU market.

The CBAM “PPA Rule”: Physical and Hourly Is the Core Message

The Commission’s practical rules for CBAM place “physically deliverable, hourly-matched clean electricity” at the centre of reducing CBAM costs.

Actual electricity emissions for goods produced outside the EU may only be used where electricity is physically supplied to the production facility. There are two mechanisms for this:

- A direct wire connection (without grid transfer), for example, a captive power plant or on-site renewable installation that supplies electricity exclusively to the production facility through a dedicated connection. Because the electricity does not mix with the grid supply, attribution is structurally clear.

- A physical PPA, where electricity is delivered through the public grid under a contract that ensures physical supply to the facility. In this case, additional evidence is required to demonstrate delivery and time alignment.

In both cases, purely financial PPAs or energy attribute certificates are not sufficient.

Source: EnergyTag.

The Real Impact on APAC: CBAM Is Quietly Rewarding “Granular Power Systems”

The biggest long-term impact of CBAM’s electricity approach is not that every APAC company will suddenly sign a PPA. It’s that CBAM is pushing a trade-linked definition of credibility that looks like this:

- Hourly (or ≤ hourly) metering becomes valuable.

- Deliverability evidence (transparent grid structures, congestion visibility) becomes valuable.

- Physical delivery structures matter more than contractual claims.

- Verification-ready data trails become a competitive asset, not just a compliance burden.

The rules could unlock demand for physical PPAs because companies exporting to the EU will face rising CBAM costs unless they reduce embedded emissions, and the Commission has made physical hourly delivery a core requirement rather than annual matching.

Practical Takeaways for APAC Companies (and the Policymakers Who Shape Their Options)

For APAC Exporters and Heavy Industry

- Map EU exposure: which products are CBAM goods (today) vs “near-adjacent” supply chain contributors.

- Audit electricity reality: do you have access to granular data (production and consumption), and is it trustworthy?

- Stress test procurement: do your electricity contracts support physical delivery claims, or are they purely financial?

- Engage EU buyers early: your buyer may be the CBAM declarant, but you control much of the evidence chain.

For APAC Power-Market Institutions

CBAM’s electricity approach implicitly favours markets with:

- Policy support that enables direct PPAs.

- Transparent congestion and dispatch information.

- Widespread smart metering and accessible granular data governance.

- Green utility products that can be structured as a deliverable and time-matched supply.

- Credible third-party verification pathways.

That is exactly the market infrastructure that makes hourly claims defensible.

CBAM Is an Electricity and Market-Design Signal, Not Just a Border Tax

CBAM is often described as a border carbon cost. But for electricity, and for electricity embedded in CBAM goods, it is also a statement about what counts as credible proof.

The emerging direction is simple:

- Grid averages are the default.

- If you want to do better than average, you must demonstrate physical delivery and hourly alignment under strict evidence and verification expectations.

For APAC exporters, this creates a new competitive pathway; if cleaner electricity can be shown credibly, it can become a cost advantage, not just a reputational claim. And for APAC power markets, CBAM strengthens the case for reforms that value time, location, and deliverability, the foundations of granular electricity accounting.

Read more about APAC readiness for granular electricity accounting here.

Annexure: What APAC Exports to the EU, and Where CBAM Electricity Rules Bite

CBAM today covers a limited set of goods, but electricity-related rules matter indirectly- because electricity is a major input into CBAM goods (steel, aluminium, cement, fertilizers, hydrogen). Further, even where APAC exports are not “CBAM goods,” CBAM is increasingly shaping buyer expectations about credible electricity-related (embedded) emissions.

China: manufactured goods dominate; electricity becomes a competitiveness variable upstream

Eurostat shows that EU imports from China are overwhelmingly manufactured goods, with machinery & vehicles a majority share.

While many of these products are not CBAM goods today, their upstream supply chains include energy-intensive materials (metals, chemicals, industrial inputs) and large electricity loads. If CBAM is extended to more ETS sectors, or if EU buyers start asking for more detailed electricity data than the law strictly requires, supply chains linked to China will likely feel early pressure.

Power system context:

- Electricity markets are partially liberalized but still heavily provincial.

- Corporate PPAs exist, but physical deliverability structures vary by province.

- Inter-provincial transmission exists, but congestion transparency is limited.

- Hourly data is available at the system level, but access for corporate verification remains uneven.

- Grid-average emission factors are improving, but still coal-heavy in many regions.

Challenge: Demonstrating physically delivered, time-aligned electricity with verifiable data is possible but not yet systemic across all provinces.

Republic of Korea: machinery/transport equipment + chemicals- closely adjacent to CBAM sectors

The EU’s trade relationship with Korea is characterized by machinery and transport equipment as the largest imports, with chemicals as a close second. This matters because CBAM goods (e.g., metals and fertilizers) and related sectors rely heavily on electricity. Korea’s exporters and their EU buyers will increasingly look at procurement structures that can show lower-carbon electricity at higher granularity, particularly where emissions significantly affect the product’s footprint.

Power system context:

- The electricity market is largely dominated by state-owned KEPCO.

- Corporate PPAs are emerging but still limited.

- Smart meter rollout is complete in 2024 with high-granularity data

- Renewable share is growing, but fossil generation remains material.

- Hourly system operation exists, but corporate-level granular access is less mature.

Challenge: Technical foundation for hourly matching is in place, but limited flexibility in electricity procurement could constrain producers seeking to demonstrate CBAM-compliant physical supply structures.

India: machinery, chemicals, base metals, mineral products, textiles

The European Commission notes EU imports from India include machinery and appliances, chemicals, base metals, mineral products, and textiles. For CBAM specifically, the “base metals” and “mineral products” buckets are the important related sectors. If Indian producers (or their EU buyers) want to avoid being treated as “grid-average by default” under CBAM, the focus shifts to how electricity is contracted, delivered, and evidenced.

Power system context:

- Open access and corporate PPAs are legally allowed.

- Physical PPAs are common in renewable energy.

- However, grid congestion and curtailment remain issues in some states.

- Granular metering exists (15-minute settlement nationally), but access to production-level hourly verification can vary.

- Government support for Round-the-Clock (RTC) renewables is a good start.

- Renewable procurement is often annual /monthly-matching focused, but evolving to hourly matching (due to the gradual removal of banking).

Challenge: India is relatively advanced in allowing physical PPAs, but providing time-aligned and deliverable electricity for specific production sites may require improved data transparency and verification systems.

Japan: machinery, motor vehicles, chemicals, instruments

EU trade sources summarize EU imports from Japan as machinery, motor vehicles, chemicals, optical/medical instruments, and plastics. Not all of these are currently covered by CBAM. However, Japanese manufacturers selling into the EU will increasingly need credible evidence of their electricity-related emissions. This matters both for regulatory compliance and for their competitive position in the market.

Power system context:

- Market liberalization has progressed.

- Corporate PPAs are growing.

- The grid is divided into multiple frequency regions.

- Congestion and zonal pricing vary.

- Granular data exists, but integration and verification may require stronger frameworks.

Challenge: Japan may be structurally capable of meeting CBAM-style requirements, but verification alignment and consistent deliverability evidence will be key.

Viet Nam: machinery/appliances plus textiles and footwear

The EU’s Vietnam trade page highlights that EU imports from Viet Nam are led by machinery and appliances (about half of total imports), plus footwear and textiles.

Although only some of these products fall under CBAM’s current scope, Vietnam is a good example of where the broader market signal is wider. EU buyers increasingly differentiate suppliers based on the credibility of energy and emissions data, particularly for energy-intensive tiers upstream.

Power system context:

- Rapid renewable build-out in recent years.

- Curtailment issues have occurred.

- Direct corporate PPAs are evolving (Private wire and virtual PPA)

- 30-min pricing exists (Full-Market-Price /FMP); DPPAs are exposed to FMP.

- 30-min metering data is available, but access is limited.

- Grid transparency and congestion reporting remain limited.

Challenge: Physical renewable supply may exist, but demonstrating time-aligned and verifiable delivery to specific production sites may be complex.

- Under Regulation (EU) 2023/956, electricity-related (indirect) emissions are not applied uniformly across all CBAM goods. Annex II of the Regulation specifies that, in the initial phase, only direct emissions are to be calculated for iron & steel, aluminium, and hydrogen. By contrast, cement and fertilizers (including ammonia) include both direct and indirect emissions in their embedded emissions calculation. ↩︎